8 Agency and Financial Incentives

Physicians play a pivotal role in influencing health care decisions, acting as agents on behalf of their patients. Patients rely on physicians’ knowledge, but financial incentives mean that doctors may not always make the same choices patients would under full information. A central policy question is therefore: how do financial incentives shape the quantity and type of care physicians provide?

In the next two chapters, we focus on financial incentives in the context of physician agency. This chapter builds a simple economic model of treatment choice to illustrate the mechanisms. In the following chapter, we will use this framework to compare alternative payment systems.

8.1 Financial incentives

Do financial incentives matter empirically? The evidence is clear: yes. Studies such as Gruber and Owings (1996) and Clemens and Gottlieb (2014) show that physician decisions respond to payment rules in ways that affect both utilization and patient outcomes.

To understand the underlying mechanics, we develop a simple model of treatment choice. Physicians are assumed to value both patient benefit and profit. We start with a case where physicians can set both the price and the quantity of services, and then turn to the more realistic case where prices are fixed by insurers or government programs.

8.2 With price and quantity setting power

We begin with a simple model in which physicians are able to set both the price and the quantity of services they provide. Let \(x\) denote the quantity of services, and let \(B(x)\) represent the benefit that patients derive from those services, with \(B'(x) > 0\) and \(B''(x) < 0\). Patients pay a price \(p\) for each unit of service, while physicians incur a constant marginal cost \(c\) for each unit delivered.

The patient’s net benefit is therefore

\[NB(x) = B(x) - px \tag{8.1}\]

and patients will only accept treatment if their net benefit is at least as large as their outside option, \(NB^0\).

The physician’s profit is given by

\[\pi(x) = (p - c)x \tag{8.2}\]

and the physician chooses \(x\) to maximize profit subject to the participation constraint in Equation 8.1. Substituting this constraint into the profit function yields

\[\pi(x) = B(x) - NB^0 - cx \tag{8.3}\]

Maximizing Equation 8.3 leads to the first-order condition

\[B'(x) = c \tag{8.4}\]

which implies that the physician selects a quantity such that the marginal benefit to the patient equals the physician’s marginal cost.

If patients could instead choose directly, they would maximize their own net benefit in Equation 8.1, which gives the condition

\[B'(x) = p \tag{8.5}\]

Because \(p > c\), the patient’s optimum occurs at a lower quantity than the physician’s. Since \(B'(x)\) is decreasing, the equality \(B'(x) = c\) in Equation 8.4 is reached at a higher level of \(x\) than the equality \(B'(x) = p\) in Equation 8.5.

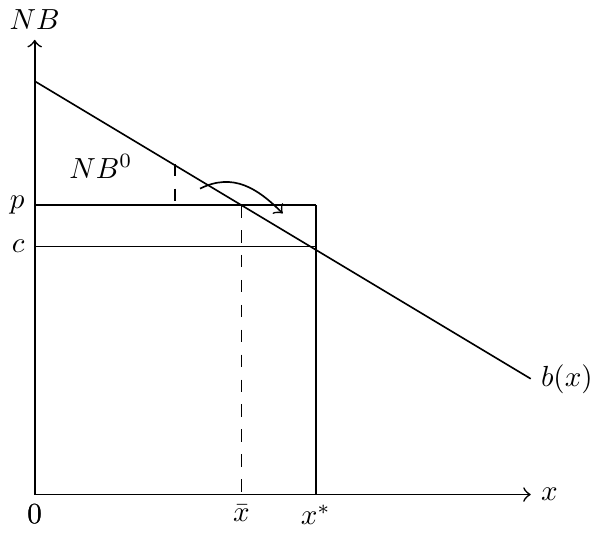

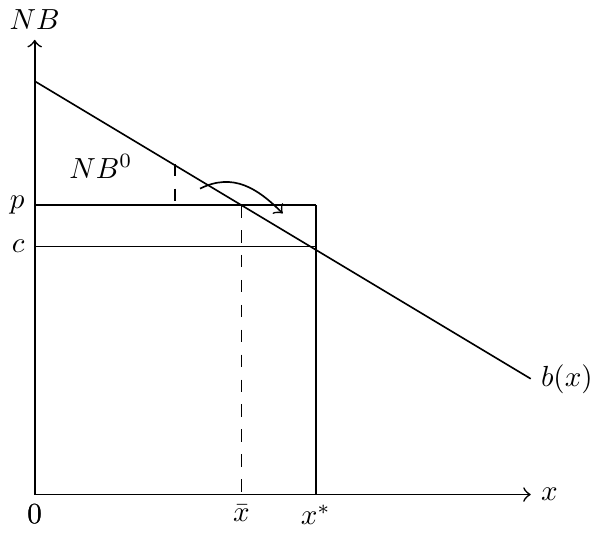

The model therefore predicts that physicians will provide more services than patients would choose for themselves. This prediction is illustrated in Figure 8.1, where \(\bar{x}\) denotes the patient’s preferred level of care and \(x^*\) denotes the physician’s choice.

8.3 With fixed prices

The two-step approach described above applies when physicians can choose both the price and the quantity of care. However, in many settings prices are fixed administratively (for example, under Medicare or Medicaid), so physicians retain discretion only over the quantity of care. In this case, we work solely from the patient’s participation constraint.

The constraint is still given by

\[B(x) - \bar{p}x = NB^{0}, \tag{8.6}\]

where \(\bar{p}\) denotes the fixed price and \(NB^0\) is the patient’s outside option.

In this setting we cannot substitute the participation constraint into the physician’s maximization problem as before, because the problem leads to a corner solution and standard derivatives do not apply. Instead, we solve directly from the patient’s participation constraint, which implies

\[x = \frac{B(x) - NB^{0}}{\bar{p}}. \tag{8.7}\]

To examine how the equilibrium quantity responds to changes in the administratively set price, totally differentiate Equation 8.7. This yields

\[\frac{dx}{dp} = \frac{-x}{p - B'(x)} < 0. \tag{8.8}\]

The comparative statics in Equation 8.8 show that an increase in the administratively set price reduces the quantity of services provided, while a decrease in price increases it.

This result highlights an important policy implication: attempts to control spending solely through price reductions may have unintended effects on service provision. Understanding how physicians adjust quantities in response to fixed prices is therefore crucial for anticipating the consequences of payment reforms.

8.4 Other Considerations

This simplified model highlights how fee for service financial incentives can shape physician behavior, and the model is valuable for understanding basic mechanisms at work. Still, there are several caveats to keep in mind when connecting the theory to practice.

First, in reality the patient’s out-of-pocket price and the physician’s reimbursement rate often differ. Our baseline model treats them as the same for simplicity, which helps keep the intuition clear, but it is important to remember that policy changes can shift one without the other. A simple two-price extension shows how the same basic framework can accommodate this distinction (see Section 8.5).

Second, physicians are not purely profit-maximizing. Altruism, professional norms, and malpractice concerns all influence choices. Including these motives would complicate the model, but the simple version still provides a benchmark against which the effects of payment incentives can be understood.

Third, outside options and local market structure shape how tightly the participation constraint binds. Greater competition or easier patient switching can reduce the scope for physician-induced differences, but the logic of the model continues to explain why payment rules systematically tilt treatment choices.

In short, this model of physician treatment decisions is deliberately stylized, but it remains useful precisely because it clarifies the underlying trade-offs. We show why physicians may provide more (or less) care than patients would choose on their own, and this helps organize thinking about how alternative payment designs might alter those incentives.

8.5 A two-price extension

The models above treat the “price” of care as if it were the same for both patients and physicians. In reality, the patient’s out-of-pocket cost and the physician’s reimbursement rate are often very different. To reflect this, suppose patients face an out-of-pocket price \(p_{pt}\), while physicians are paid \(p_{md}\). Let \(c\) again denote the physician’s marginal cost of providing care.

The patient’s net benefit is

\[NB(x) = B(x) - p_{pt}x, \tag{8.9}\]

and patients will accept treatment only if \(NB(x) \geq NB^0\). The physician’s profit is

\[\pi(x) = (p_{md} - c)x. \tag{8.10}\]

Maximizing profit subject to the participation constraint gives

\[B'(x) = c, \tag{8.11}\]

so the physician’s choice depends on cost rather than the patient’s out-of-pocket price. If patients could choose directly, they would instead maximize Equation 8.9, leading to the condition

\[B'(x) = p_{pt}. \tag{8.12}\]

This simple extension clarifies several empirical patterns. When \(p_{md}\) increases, holding \(p_{pt}\) fixed, physicians have stronger incentives to provide care and utilization tends to rise. When \(p_{pt}\) increases, holding \(p_{md}\) fixed, the patient’s participation constraint tightens and feasible utilization falls. Similarly, a higher outside option \(NB^0\) moves utilization closer to what patients would otherwise choose.

In practice, policy reforms often move \(p_{md}\) and \(p_{pt}\) independently—for example, Medicare adjusts administered fees to physicians while patient cost sharing is determined by separate program rules. Distinguishing these two prices helps reconcile the theory with evidence on how physicians and patients respond differently to payment changes.