7 Physicians as Gatekeepers

The U.S. health care system, like its insurance system, is unique in many ways. One of its defining features is its fragmentation and heavily decentralized nature. As such, individual health care experiences differ dramatically across and even within geographic locations. The purpose of this chapter is to provide a basic understanding of the organizational structure of the U.S. health care system, focusing in particular on the role of physicians in health care delivery.

7.1 Basic Structure of Health Care Delivery

Health care delivery in the United States involves a wide range of players—physicians, nurses, hospitals, prescription drugs, rehabilitation, long-term care, and ancillary services such as laboratories and imaging centers. While all of these components are important, physicians occupy a central position: they shape treatment decisions, coordinate care, and direct patients through the system. To understand variation in physician practice patterns, it is useful to highlight several structural features of health care delivery that influence how physicians make decisions.

Training and specialization. The organization of medical education—medical school, residency, and fellowship—affects future practice styles. The divide between primary care and specialist training creates distinct roles within the system, and referral flows determine how patients move between providers. These pathways of training and referral help explain why similar patients may receive very different care depending on which physicians they encounter.

Organizational affiliation. Physicians practice in diverse organizational settings. Some are self-employed in solo practice, others work in group practices, and an increasing share are employed by hospitals or insurers. These affiliations shape autonomy, access to resources, and financial incentives, which in turn affect how physicians diagnose, treat, and refer patients.

Physician–hospital interactions. Many treatments require coordination between physicians and hospitals. The hospital sector itself is heterogeneous—general acute-care hospitals, rehabilitation hospitals, children’s hospitals, orthopedic and cancer centers, long-term care hospitals, stand-alone surgery centers, and emergency departments. Physicians’ decisions about where and how to admit or refer patients vary across this landscape, as does the balance between inpatient and outpatient care.

Ownership structures. Finally, both hospitals and physician organizations differ in ownership: government-run, private not-for-profit, private for-profit, or private equity-owned. Ownership influences institutional priorities, investment decisions, and sometimes service availability. Physicians practicing within these environments may therefore face different constraints and incentives.

Taken together, these dimensions—training, organizational setting, hospital interactions, and ownership—illustrate how the basic structure of U.S. health care delivery provides multiple channels through which physician decisions can vary.

7.2 The Role of Physicians

Against this backdrop of a fragmented and varied delivery system, physicians hold a pivotal role as “gatekeepers.” Because patients typically enter the system through a physician encounter, doctors become the key actors who translate the structure of health care delivery into individual treatment decisions.

They are often the entry point into the system, whether through primary care visits or emergency departments. Primary care physicians refer patients to specialists and ancillary services. Specialists in turn refer patients to other specialists, order imaging or laboratory services, and may decide on the location of surgeries. Hospitalists and specialists also coordinate follow-up care after inpatient stays. Across all of these encounters, physicians are responsible for selecting medications and determining treatment intensity.

This centrality gives physicians disproportionate influence. They possess more knowledge than patients about medical conditions and treatments, and this asymmetry means patients rely heavily on physicians to guide choices. This is the classic problem of physician agency: physicians act as “agents” making or recommending health care decisions on behalf of their patients. The central question is whether those decisions align with what patients would have chosen under full information, or whether financial incentives, practice norms, or other factors lead to divergence.

7.3 Variation in Health Care Utilization

The implications of physician agency are evident in the remarkable variation in health care utilization and spending across geographic regions. Patients may encounter different patterns of treatment simply because of the preferences and practice styles of the physicians they see. These differences cannot be explained by patient health alone. Instead, they reflect systematic differences in medical culture, local capacity, and financial incentives.

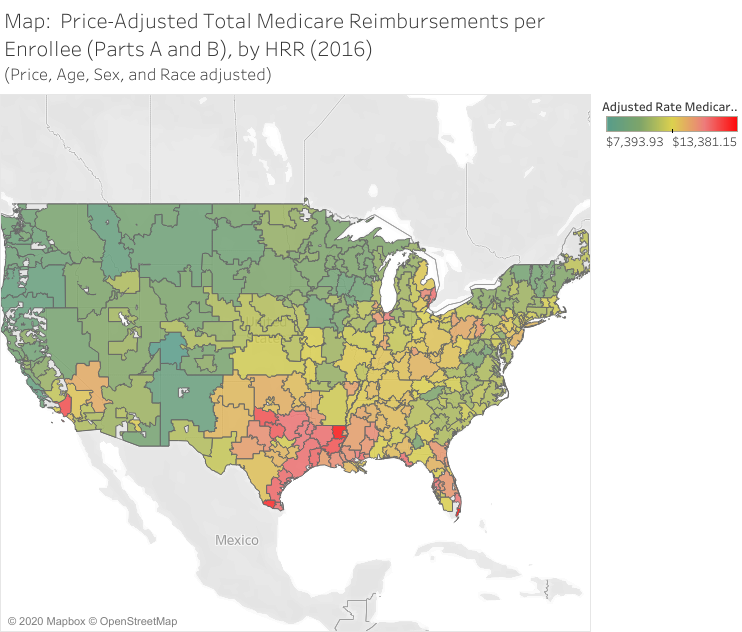

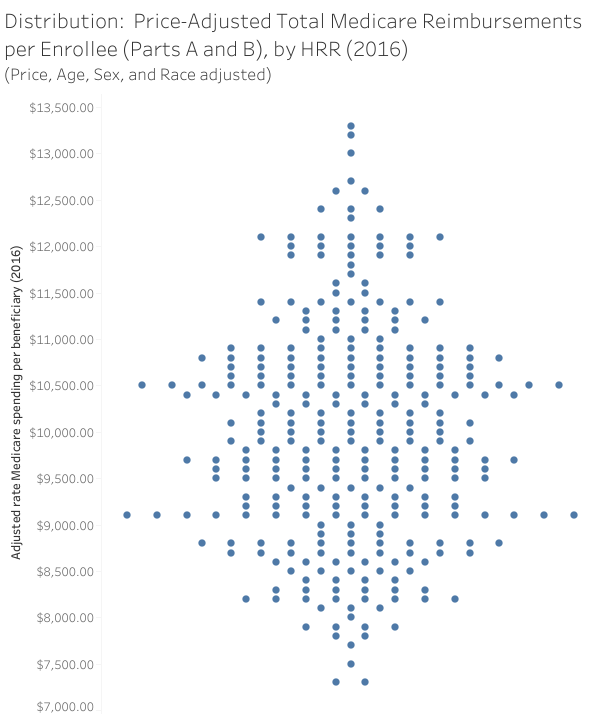

The Dartmouth Atlas of Health Care has documented this variation extensively. Medicare spending per beneficiary differs substantially across regions, with some areas using far more hospital and physician services than others. These patterns are visible both in maps of regional spending (Figure 7.1) and in distributions of per-beneficiary spending (Figure 7.2).

Such variation inevitably raises questions about waste in the health care system. Estimates suggest that more than 30% of U.S. health care spending yields little or no clinical benefit. Examples include payment differentials based purely on treatment location, overuse of advanced imaging with limited diagnostic value, inappropriate use of proton therapy for cancers where conventional treatment is equally effective, unnecessary placement of coronary stents in low-risk populations, and the performance of arthroscopic knee surgery where physical therapy may be a better option.

However, identifying waste prospectively is extremely difficult, with many assessments made only in hindsight, once evidence about patient outcomes is available. Nonetheless, the presence of large geographic variation combined with clinical studies of low-value care underscores the importance of understanding physician decision-making and incentives. Physicians are not just providers of services; they are organizers of treatment pathways, and their decisions shape both the costs and the outcomes of health care delivery, making physician behavior a central concern for health policy.